Debate regarding the origins of the infamous silk road

Introduction

Throughout the advent of modern history, there has been a debate regarding the origins of the infamous silk road, the commencement of the trade routes, who and what comprised of it and what all was traded on that route. After the scrutinization of the abundance of literature on the silk road, various scholars have tried to come up with an exact definition of it. The German geographer, Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen first coined the term ‘Die Seidenstrassen’ or the silk road to describe the trade routes linking China, India, and the Mediterranean throughout Central Asia and the majority of Euroasia.[1] Even though such a definition is a very vague in as it only describes the broader regions of the silk route and not the intrinsicalities of it, but for the following essay, this definition would suffice. The primary commodity was said to be silk that travelled through the Chinese borders, to India, and ultimately to the Roman and Persian empires as there was heavy demand for it there, but silk was not the commodity that was exchanged, there is evidence regarding the exchange of precious gems, glass, livestock, Buddhist art, spices etc. as well.[2] However, for all this to start, there was a rise in the nomadic agriculture along the silk route. The primary argument of the following essay provides evidence and establishes the fact that certain aspects of geography and ecology of Central Asia led to the rise of pastoral nomadism and irrigation agriculture along the lines of silk route, and this, in turn, led to the increase in trade on the silk route. To cement this argument, various factors like that of water availability, mountain cover and the terrain of the surrounding regions will be scrutinized.

Pastoral and Nomadic Societies

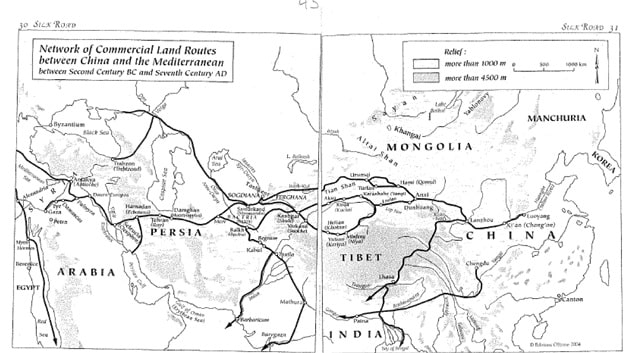

Figure 1 Network of Commercial Land Routes on the Silk Road[3]

The figure 1 above elaborates the expanse of the Silk Road which practically connected the two continents of Europe and Asia together, coining the term as Eurasia. The Silk Road traveled a distance of 7000 miles, where the goods primarily moved from the eastern part of the continent, that is China and India to the western counterparts of Persia and Rome, commencing from 200 BC to the 14th Century AD and connecting the Yellow River in China to the Mediterranean Sea[4]. However, the most dominant route of commerce, that is the waterway, was not preferred during the early phases of silk road due to the fact that majority of the rivers originated from the Tundra region and drowned in the seas in a frozen state alone. Other waterways present on the Silk Road were either not fit for navigation or were merely seasonal. However, the question would be raised regarding how the Silk Road grew its reach by primarily using the land routes alone. The answer lies in the fact that there was a rise in the nomadic and pastoral culture along the silk route due to various geographical factors present there, especially in the regions surrounded by Central Aisa. Pastoral societies have been defined as the societies which have disproportionate means of existence and heavily dependent upon the herding of domesticated livestock[5]. However, these pastoral societies can even be termed as nomads due to their diverse settlement patterns but they did not wander without a purpose. Majority of the nomads travelled primarily for trade purposes, where majority of their traded belonged to exchanging of their herds for other vital commodities and they soon started to settle along favourable terrains on the silk road, developing into societies, one of the largest out of them was the Mongol pastoral society in the 13th century BC, which dominated a major chunk of the Silk Road history in Eurasia[6]. This answers the question as to why the majority of the commercial trade routes in the early phases of the Silk Road were land dominated has been answered by painting a picture of the pastoral and nomadic society. However, one question that still needs some explanation is that how did these societies flourish in the rugged terrains of the Silk Road?

Ecology and Geography of the Silk Road

Even though, an abundance of literature focuses on the fact that the Silk Road led to the settlement and flourishing of many societies, the journey to it was not an easy one. Due to the vast area on which trade was conducted on the Silk Road, there were various geographical factors such which created a hindrance travelers as well as traders. Various mountain ranges, namely, Tianshan, Pamirs, and Kunlun created a major hindrance due to their altitude and arid regions which comprised of passes which were essential, yet dangerous to the trade routes[7]. The second problem was posed by the desert areas such as those in the Taklamakan, located in the modern day Xinjiang province of China where there was a high scarcity of water with which came the limitation of waterway navigation. Even after such adversities, the same route even provided for favorable factors such as the coniferous forests, steppe belt, and oases, helping the nomads in accessing vast grasslands for irrigation and other trade-related purposes.

The Heartland of Eurasia

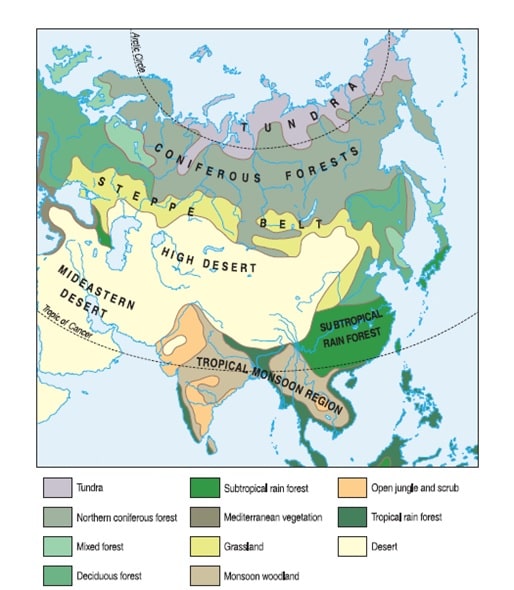

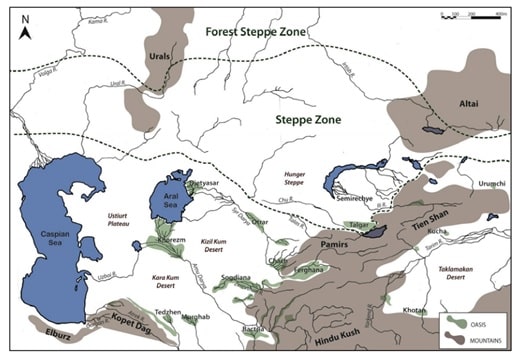

Figure 2 Ecological Zones of Eurasia[8]

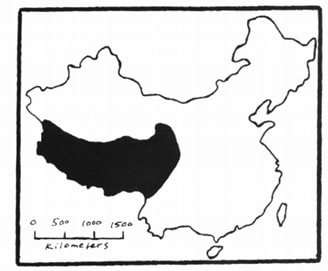

Eurasia is a geographical term coined to interlink the two continents as mentioned above, but the heartland or the central node of it lied in the exploitation of resources in regions of Central Asia. One of the major reasons for the exploitation of resources by the pastoral and nomadic societies lies in the various geographical factors present there. The geography of the Silk Road, or more precisely that of Inner Asia as shown in figure 2, comprises of a complex interaction of physical features such as mountains, the grasslands of the steppe and the river valleys or oases[9]. The mountain zone of Inner Aisa comprises of a lot of ranges but they are more or less homogenous, which played to the advantage of the pastors because of the uniformity in climate. This is so because, throughout the year, the majority of the climate remains cold, giving the pastors a clear distinction between regions which are suitable for herding. Tundra was the major mountain region on the Silk Road consisting of the modern day northern Siberia, which has a close proximity to the Arctic currents, resulting in a year-round cover of cloudiness and high fog density. When it comes to vegetation, the Tundra has a sparse vegetation of perennial plants like moss, lichens and dwarf shrubs with a minor cover of birch trees. Such a vegetation pattern provides for animals like elk and reindeers to prosper in the snow cover, which in turn provide for the need of nomads in that region, where they practice reindeer herding. This is also supplemented by hunting of fur based animals in that region and using them for trade[10]. One of the examples of pastoral nomadism in the mountain regions can be seen in the Tibetan plateau in the modern day Western China. Figure 3 illustrates the region where pastoral nomadic tribes are still active and indulge in various activities ranging from animal grazing on the higher altitudes to farming activities in the foothills[11].

Figure 3 Tibetan Pastoral Nomadic Area in Western China11

The coniferous forests or the coniferous forests of Taiga can be broadly divided into four primary physical segments, namely, the lowlands covering the Pacific sea, East of the Urals (majorly towards the West Siberian lowlands), the Siberian Uplands and the mountains covering the southern borders of Siberia as well[12]. As depicted in figure 2, the location of these forests put them under a subarctic climate as well, hence, the forests experience the same prolonged winter climate as there was in the Tundra ranges. With a region covering 6000 miles, these forests also provide for the world’s largest tree cover but do not have a wide variety of flora and fauna. Due to the precipitation levels in the forest, it became difficult for the nomads to hunt or gather in these forests. The majority of the nomads in such an ecology, survived primarily through hunting and trading in the meat of reindeer, elk, deer. The nomads and pastors of the regions of both the Tundra and the coniferous forests were small in communities and did not evolve into sophisticated traders as well. However, they comprise an important element of the pastoral and nomadic culture on the Silk Road and further provide an evolutionary roadmap to the more specialized nomadic communities and agriculture societies.

The steppe belt was the most crucial geographical region which thrived due to its immense population of flora and fauna. It can be divided into three segments, the wooded steppe, the grasslands in the middle and the desert steppe in the southern belt. Due to the homogenous topography of the grasslands, which comprised of vast areas of flat plains, it was the most traveled routes by the nomads as well as traders. Even though there were five thousand species of plants that grow in the Central Asian Steppe under the influence of, but not all of them were used for grazing purposes alone. The diversity in the natural conditions in the steppe range from the Danube Region, where the extremely fertile black soil differs from that in the semi-desert of Ryn-Sands. The uniqueness the steppe belt lies in the climate and the moisture pattern there, with an annual precipitation of 500mm, which led to the growth of vegetation, which was drought averse, narrow leveled and very suitable for grazing[13]. This even lead to the high annual decay of the plants, which got mixed with the soil to make it rich in humus. This trait is not homogenous as the fertility of the soil varies from region to region and hence the farming patterns differed as well there. The domesticated animals of the steppe provided for the major trade commodity for the nomads there, especially the horses that were bred there were sold for good prices. Due to the aforesaid advantages in terms of flora and fauna in the steppe belt, it became a major interaction zone for both the nomads, pastures and it even leads to the increase in pastor societies in and around the steppe region.

Irrigation Agriculture

Central Asia is comprised of a lot of regions which are arid in their groundwater content as well as their yearly rainfall. However, the arid regions of Central Asia have some well-watered zones known as desert Oases[14]. These oases have in turn led to the rise of settlements around these areas, due to increasing irrigational practices, which can be dated back to the fifth millennium B.C.E. Figure 4 highlights the major desert oases in Inner Eurasia’s regions.

Figure 4 Inner Eurasia's Desert Oases[15]

Further evidence from archaeologists has revealed that there was substantial exploitation of the new agriculture land found around these oases and such oases started to expand, especially in the Christian Era of the Silk Road. With the discovery of new resources and regions, especially in the northern area of Central Area, the southern province of Zerafshan and the middle reach of the Syr Darya and Tashkent oases, nomadic societies in large numbers decided to settle down[16]. These nomads were primarily engaged in the activities of livestock breeding and herding and decided to settle down due to the economic potential of the agricultural trade. Sophisticated irrigation practices picked pace during the Kushan Era of the Silk Road where the region in upper Zerafshan and Vaksh valley in modern-day Tajikistan. Evidence has been found on the fact that these valleys had been watered by the Dzhuibar canal, built in the second century A.D[17]. The Kushal Era also saw the irrigation system developed in the lower regions of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya where entire system of canals was developed the oases water was exploited for heightened agriculture activities and societal resettlement. These facts show that the trend from pure pastoral or nomadic societies bent towards a more settled and an agricultural way of life for the people on the silk road, especially in the Central Asian region. Factors such as the presence of desert oases as well as the climate of the region led to the flourishing of various societies.

As societies moved more towards an agrarian lifestyle, there were more and more opportunities for trade between people. An example of this can be seen in Turfan, where around hundred varieties of grapes used to grow with the help cultivation from the oases water which was supplied through well-organized irrigation channels[18]. Due to the vast expanse of the Silk Road, it was impossible for one trader or farmer to deliver his commodity to a consumer at the other end of the continent, hence there were middlemen who specialized in regional as well as product trading. The major reason for an increase in trading activities on the Silk Road was the diverse climate and ecology which encompassed every region in a different manner. Due to this, there was no homogeneity in the commodities that were produced, hence barter trade was extremely prominent on the Silk Road. Soon every region started to specialize in a few products and further started to depend upon the trade along the Silk Road to acquire commodities which they needed. This way, the climate and ecology of a region defined the societal occupation residing there, and in turn, decided the specialization of products that were to be traded.

Conclusion

There is a vast amount of literature that has surmounted on the Silk Road, its inhabitants, the ecology etc. and not even a fraction of it was analyzed for this essay. However, with the evidence provided by various scholars, the argument of the essay, which revolved around the ecological impact on the increase of pastoral and nomadic societies could clearly be determined. Further, a clear relationship of the ecological factors has been established with that of the rise in irrigation agriculture and subsequent increase in trade along the Silk Road. The essay also provides a brief regarding how a pastoral and a nomadic society is defined and what are the features of it. Moreover, the ecological impact has been studied in a concentrated region of Central Asia and bifurcated according to various regions like the Tundra region, the coniferous forests and the steppe belt. All these regions have been studied separately while highlighting their topographic advantage and disadvantage, and what were the major nomadic occupation in those regions and how they either flourished or remained stagnant.

Bibliography

Behera, S., 2002. India's Encounter with the Silk Road. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.5077-5080.

Brite, E.B., 2016. Irrigation in the Khorezm oasis, past and present: a political ecology perspective. Journal of Political Ecology, 23(1), pp.1-25.

Boulnois, L., 2004. Silk road: monks, warriors & merchants on the Silk Road. WW Norton & Co Inc.

Christian, D., 2000. Silk roads or steppe roads? The silk roads in world history. Journal of world history, 11(1), pp.1-26.

Christian, D. and Benjamin, C., 1998. Worlds of the silk roads: ancient and modern: proceedings from the Second Conference of the Australasian Society for Inner Asian Studies (ASIAS), Macquarie University, September 21-22, 1996 (Vol. 2). Brepols Pub.

Higham, C., 2014. Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing

Hill, J., 2006. The Silk Road Revisted: Merchants and Minarets. s.l.:Author House.

Kuzmina, E.E., 2008. The prehistory of the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Liu, X., 2010. The Silk Road in world history. Oxford University Press.

Miller, D.J., 1999. Nomads of the Tibetan Plateau rangelands in western China. Part Two. Pastoral production practices. Rangelands Archives, 21(1), pp.16-19.

Mukhamedjanov, A.R., 1994. Economy and social system in Central Asia in the Kushan Age. History of civilizations of Central Asia, 2, pp.265-290.

Perdue, P.C., 2009. China marches west: the Qing conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press.

Richerson, P.J., 2001. Chapter 5: Pastoral Societies. Principles of Human Ecology, pp.79-80.

Sinor, D. ed., 1990. The Cambridge history of early inner Asia (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Waugh, D. C., 2017. The Silk Roads and Eurasian Geography. [Online] Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/geography/geography.html [Accessed 15 December 2017]

Wendelken, R. (2007) Geography and the Silk Road. Available at: http://asianetwork.org/ane-archived-issues/2007-winter/anex2007-winter-wendelken.pdf (Accessed: 15 December 2017).

[1] Christian, D., 2000. Silk roads or steppe roads? The silk roads in world history. Journal of world history, 11(1), pp.1-26.

[2] Liu, X., 2010. The Silk Road in world history. Oxford University Press.

[3] Boulnois, L., 2004. Silk road: monks, warriors & merchants on the Silk Road. WW Norton & Co Inc.

[4] Behera, S., 2002. India's Encounter with the Silk Road. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.5077-5080.

[5] Richerson, P.J., 2001. Chapter 5: Pastoral Societies. Principles of Human Ecology, pp.79-80.

[6] Christian, D. and Benjamin, C., 1998. Worlds of the silk roads: ancient and modern: proceedings from the Second Conference of the Australasian Society for Inner Asian Studies (ASIAS), Macquarie University, September 21-22, 1996 (Vol. 2). Brepols Pub.

[7] Wendelken, R. (2007) Geography and the Silk Road. Available at: http://asianetwork.org/ane-archived-issues/2007-winter/anex2007-winter-wendelken.pdf (Accessed: 15 December 2017).

[8] Perdue, P.C., 2009. China marches west: the Qing conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press.

[9] Waugh, D. C., 2017. The Silk Roads and Eurasian Geography. [Online] Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/geography/geography.html [Accessed 15 December 2017]

[10] Sinor, D. ed., 1990. The Cambridge history of early inner Asia (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

[11] Miller, D.J., 1999. Nomads of the Tibetan Plateau rangelands in western China. Part Two. Pastoral production practices. Rangelands Archives, 21(1), pp.16-19.

[12] Perdue, P.C., 2009

[13] Kuzmina, E.E., 2008. The prehistory of the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press.

[14] Higham, C., 2014. Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing.

[15] Brite, E.B., 2016. Irrigation in the Khorezm oasis, past and present: a political ecology perspective. Journal of Political Ecology, 23(1), pp.1-25.

[16] Mukhamedjanov, A.R., 1994. Economy and social system in Central Asia in the Kushan Age. History of civilizations of Central Asia, 2, pp.265-290.

[17] ibid

[18] Hill, J., 2006. The Silk Road Revisted: Merchants and Minarets. s.l.:Author House.