Aspects Of Unity Assignment Help

The aspects of Unity contribute collectively to a satisfactory visual whole. They should not be seen as a check list, but rather as number of inter related requirements the importance of which is partly subject to individual preference and greatly influenced by other principles of design. The aspects of Unity are dominance or self-unity, harmony, vitality and balance.

A simple object such as a sphere or an egg is an obvious visual entity having self unity. Fishes and birds, like submarines and aircraft, are subject to aerodynamic and hydrodynamic forces which impose upon them a simplicity of form. This gives an effect of self unity- at least at a distance. Simple buildings can produce a similar effect: an isolated crofters cottage for instance. However, as we look more closely at an aircraft or a cottage, what appears simple at a distance is seen to contain a number of visual elements which arise from the detailed requirements of function and stability. So roofs, walls, windows and doors all provide colours, tones, textures, direction, solid to void etc. As the visual elements increase, there is a greater tendency for competitions to arise. Thus we find a need for a visual dominant as a means of avoiding dualities or competitions of equal interest.

Dominance- This may be provided by the effect of one colour, tone or texture being visually stronger than the remainder. A dominance of direction would mean that the horizontals were stronger- collectively- than the verticals or, alternatively, that there is a dominance of verticality. A dominance of solid over void or vice versa is necessary to avoid an equal competition which would tend to destroy unity. A dominant form or shape can help to provide a sense of unity. Quite obviously, unity cannot exist if there is a duality or competition of visually equal elements. A students early work is often preoccupied with simply avoiding dualities and pluralities. The difficulty, and one of the reasons why so much practice is necessary, is that while we are trying to overcome one visual weakness we frequently lead ourselves into producing others. For dominance is only one aspect of unity and, as we must constantly remember, our visual objectives must be achieved with due regard for the demands of other principles.

Harmony- This is the next aspect of unity. Colour harmony means what it says; colours being related by being near to each other in the colour wheel (or colour solid), that is to say colours which are associated with one hue, e.g. browns, golds and yellows all near to yellow hue sector. Harmony of texture may mean simply a matching textural quality although, with the bolder textural effects of some materials, even carving, we can associate some textures, e.g. ribbing, as being related even ehen they are not identical. Tones can be harmonious only in the sense of being of equal tonal value. Some recent graphic art has employed colour change- contrast in combination with equal tones. In architecture there is usually a tendency to use a more harmonious colour range in combination with tonal contrast. There is no particular reason why this should be so, except that when there is a little sunlight a lack of tonal change produces a rather dull sunless effect. It may be worth noting that when we use two materials together, e.g. brickwork and concrete, we are in fact introducing colour, textural and tonal changes simultaneously. If this is not appreciated in advance, and drawings may not always show this effect, we can find that we have produced multiple competitions of equal elements. Harmony of direction at its simplest may mean simply the same direction. In a complex composition the directional forces arise from a number of materials and components, even the spaces or solids between them, and we must learn to measure and relate the directional effect produced by our designs. The direction provided by the total building shape must be seen in relation to the elements within it. An equal effect of direction between the two will form a visual duality.

Proportion can be a powerful element in providing harmony of composition. This is particularly so in three dimensional design. The influence of Plato and the Pythagoreans is believed to have affected the architecture of Greece, although the philosophers were seeking a basis of universal or cosmic harmony. Greek design was strongly influenced by a concern for harmoniously modulated composition. The harmonic relationship of part to part and part to whole was based upon proportional systems, the best known being the golden section or divine proportion. As a geometric progression it is analogous to the spiral curve of organic growth. Thus, the golden section ratio can act as the key proportion for the development of a whole series of related shapes.

Aspects Of Unity Assignment Help By Online Tutoring and Guided Sessions from AssignmentHelp.Net

However, although the subject of harmonic proportion is fascinating and capable of very detailed study, it is only part of one aspect of unity. Certainly it is possible to develop whole networks of proportional relationships as did Le Corbusier in his Modulor. The important point for architects is that this is concerned with proportion and should not be confused with modular co-ordination which is related to dimensions. In considering the principle of unity we should attempt, wherever possible, to see our designs in terms of proportion and consider harmonic relationships where appropriate and possible. The pressures of technical integration have forced architects to concentrate more upon dimensional co-ordination of details. Too often our concern for proportion has been eroded by such factors. If anything, proportional relationships are simpler than in the past and yet, paradoxically, have been given much less consideration. If nothing else is attempted it is worth analyzing our designs in terms of proportion to study the extent to which shapes and spaces have been, or could be, related to one another.

Rhythm- repetitions of forms or shapes can be used to produce rhythms- a particularly useful way of providing harmony. However, any repetitions taken too far without change, any colour tone or texture used without relief, will eventually tend to monotony. This, in turn, will destroy unity.

Vitality- This is given by interest and in visual design, this aspect of unity is provided mainly, but not exclusively, by contrast.

Contrast of colour, tone or texture, of direction or proportion, between solid and void, can all give interest and vitality to a design. But just as harmony taken too far can lead to monotony, so too much contrast or too many contrasting elements will impair harmony and tend to produce a multiplicity of equal interests. This in turn reduces any dominance and weakens unity. Too blatant a contrast will tend to duality, the use of too many different elements leads to visual chaos.

Classical and Gothic architecture provide many examples of harmony and vitality combined to the benefit of both, in particular, the use of rhythms which contain contrasts. Modern architecture tends to use bolder contrasts, and, while this must be expected with simple forms, there is often a tendency to blatant contrast which produces a striking initial interest, but one which quickly palls. The size and form of many larger buildings makes the element of direction of particular importance. Strong direction overall or in banding of the elevation is given vitality by the contrast in direction of smaller components. Care must be taken to avoid competitions of direction and one should clearly dominate.

Compared with many historic examples, some buildings today seek vitality at the expense of harmony. This is not to say that our designs should be dull, but we must remember that a building is in being much longer than it exists on our drawing boards. This means we should seek to provide more subtle interest. Nature provides the designer with many inspirations for the integrations of harmony and vitality. We can find examples in any plant or shrub, any animal or bird and in any pastoral scene. Note how the various forms provide rhythms combined with tonal or colour harmony and contrast. This fusion of Unity with function and stability in nature is of Assignment the ideal design synthesis, something we may emulate but rarely equal.

Balance- The last aspect of unity is balance. In architecturethis is not usually a problem as the requirement for movement, under function, and of structure, under stability, lead us towards a balanced massing at least. Nevertheless, a design can be lacking in balance even though other aspects have been satisfied. Hence we must consider balance as a separate objective. It is seldom possible to correct a lack of balance in massing by minor adjustments in the composition, but usually requires some reconsideration of the whole design concept- if this is possible. Of Assignment, we have to be able to appreciate a general view of a design to appreciate this aspect. In crowded urban sites it is sometimes difficult to provide a balanced massing and pointless, too, if it cannot be seen. Finer effects of balance can be given by the effective visual weight of elements and the positions of solid and void.

So much for the essentials of Unity. For the student, it is merely a statement of a vocabulary of composition. Expertise will only develop with practice and that practice must include the integration of other principles.

Perception

Our examination of the principle of unity was concerned with the syntatics of design: that is, the visual relationship between each part and between each part and the whole composition. Our response to unity may produce a sense of pleasure or satisfaction when the composition itself is satisfying. However, apart from the visual order of a design, we respond to what we see according to previous influences or experience; the semantics of design- perception.

To the extent which we share experiences, so we share the sense of expressiveness provided by a building. It must be accepted, of Assignment, that each individual is unique and therefore will tend to differ in his response, depending upon the extent to which his background and experience differ from those of others.

In any group, society or culture, there is a large area of common influence. Each individual overlaps a major part of that common area, but may have some unique influences lying outside the normal or general experience.

Upbringing, religion, education, reading and television, provide many instances of shared perception. Spheres of interest will occur at different levels also. Local and group perceptions occur through daily contacts with others, sometimes producing specialized or esoteric interests related to sport, work or intellectual pursuits.

Our response to perception may be partly subjective, particularly where early influences have become subconscious. Nevertheless, there are some aspects of expressiveness which we can examine objectively and any framework of architectural theory must include perception as a principle, even if some of its influences are abstruse.

Because, when we look at a building, we respond to its composition and its perception simultaneously, it is to be expected that the two effects are confused by most observers. For the student of architecture the understanding and control of composition often becomes possible only as a result of an appreciation of the differences between syntatics and semantics.

Colour

Colour is the visual perceptual property corresponding in humans to the categories called red, blue, yellow, green and others. Color derives from the spectrum of light (distribution of light power versus wavelength) interacting in the eye with the spectral sensitivities of the light receptors.

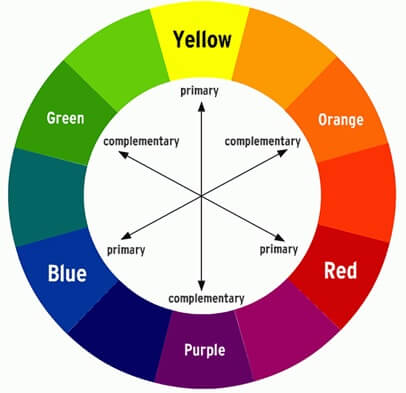

In the visual arts, colour theory is a body of practical guidance to colour mixing and the visual effects of a specific color combination. In the visual arts, colour theory is a body of practical guidance to colour mixing and the visual effects of a specific colour combination. There are also definitions (or categories) of colours based on the colour wheel: primary color, secondary color and tertiary colour. There are also definitions (or categories) of colours based on the colour wheel: primary colour, secondary colour and tertiary colour.

Value, hue and chroma are standard terms used in the colour industry to describe the three dimensions of color. Understanding value, hue and chroma is necessary for successful colour adjustment.

Value (lightness or darkness)

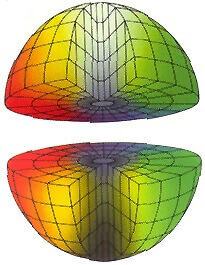

This dimension refers to the degree of lightness or darkness of the colour. The value scale runs up and down the north/south axis of the color sphere, with the whitest at the top, gradually darkening shades of gray in the middle and the blackest black at the bottom.

Hue (colour)

This dimension, which is the colour we see, moves around the outer edge of the color sphere. It moves from yellow, to red, to blue, to green. Colours can move counterclockwise on the hue scale (i.e. a blue can be moved toward the red side and become a purple). Colours also can move clockwise on the hue scale (i.e. a blue can be moved toward the green side and become aqua). By the same token, a red can be made either bluer (purple or maroon) or more yellow (orange). A yellow can be made redder (orange) or greener (chartreuse).

Chroma (intensity, richness, saturation)

Sometimes called saturation, chroma refers to a colour's level of intensity and richness. This dimension moves along the spokes that radiate outward from the central gray axis of the colour sphere. Weak, washed-out colours with the least chroma are at the core of the colour sphere, while highly chromatic colours that are rich, vibrant and most intense are at the outer edge. A rich, pure red therefore is further away from the gray central axis than a red with less chroma.

Colour wheel

The typical artists' paint or pigment colour wheel includes the blue, red and yellow primary colours. The corresponding secondary colours are green, orange and violet or purple. The tertiary colours are redorange, redviolet, yelloworange, yellowgreen, blueviolet and bluegreen.

A colour wheel based on RGB (red, green, blue) or RGV (red, green, violet) additive primaries has cyan, magenta, and yellow secondaries (cyan was previously known as cyan blue). Alternatively, the same arrangement of colours around a circle can be described as based on cyan, magenta and yellow subtractive primaries, with red, green and blue (or violet) being secondaries.

Colour scheme study

Mere theoretical understanding of colours does not automatically lead anyone to the mastery over the colour schemes. Before one experiments with colour schemes, he should be aware of the theories about simultaneous contrast, colour proportions and contrast of value, intensity and hue. Assignment of colour on two-dimensional surfaces is meaningless for architects. The colour schemes have to be implemented in the space. The study of colour on three-dimensional form is of more relevance to an architect, as compared to a painter or fine artist. Application of colours on built-up form is totally a new field. Buildings are much larger in size and scale as compared with the largest ever painting done by any painter. Buildings are seen in the dark & in the sunlight and have to look interesting throughout the day. Receeding and projecting surfaces and weather frames cast shade and shadows on the surface of the building and create several other tones, tints and shades. Students should be made aware about the present trends and fashions. Prevailing fashions in colours put restrictions on the designer. There is also a sensory and psychological impact of colour on the human mind. That is why brown is called masculine colour whereas purple and pink are the feminine counterparts. White enlarges the object, whereas black makes it look compact and sharp. Green indicates fertility whereas yellow colour shows happiness and gaiety. Royal blue is used for aristocracy whereas navy blue makes the surface week and bloodless. It is noteworthy that architects prefer to be less colourful in their external building faces, whereas interior designers use colours more liberally and aggressively. It is also interesting to check whether the images in our mind are colourful. Can the architectural spaces be influenced by enclosing it with coloured planes?